I gather that a salaryman is specifically a "businessman" and, moreover, that it really means "yuppie businessman." That is, a salaryman is, well, Alex P. Keaton along with the dress, the moderately conservative politics, the dedication to the corporate culture, the fairly traditional marital arrangements, and so on and so forth.

Is this correct? It seems so . . . 1950s!

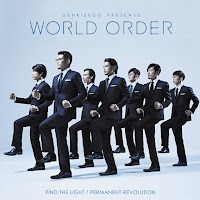

But it does make World Order even funnier.

Eugene: I would sub-categorize the term "white collar" into "salaryman" and "professional," the latter often carrying the title "sensei."

Before interviewing for the job, our salaryman-to-be submitted a resume based on the JIS resume form. Yes, there is a JIS (Japanese Industrial Standards) form for resumes. That right there tells you a lot. Even if he's applying for a part-time job at 7-11, he'll probably use that standard form.

The salaryman is the man in the gray flannel suit (well, black). He interviewed in that suit during the early spring or late summer hiring seasons and now commutes to work every day wearing the same uniform (white shirt, dark suit, and tie). He is very much a "suit" and his life henceforth belongs to the company.Kate: Moving to one of those sub-categories, lawyers pop up in many manga. In What Did You Eat Yesterday, Shiro works at a firm run by a mother and son. The son, “junior sensei,” actually can't take the lead in a trial, so Shiro--who is "A" listed, not "B" listed--has to help him out. Very British, yes?

If he does as he's told competently enough, he can expect raises on a regular timetable. The professional at the other end of the scale is promoted based on skill. There are a lot of gradations between pure seniority promotion and pure merit promotion, with the emphasis slowly shifting from the former to the latter.

Japanese companies still offer (in principle) lifetime employment. Though the old practices of parking an unproductive employee in a "window seat" (madogiwa zoku) or transferring him to the boonies are slowly fading away, both employers and employees continue to emphasize job security over remuneration.

But unlike the "good old days" (the second half of the 20th century), firings and layoffs are more common now during economic downturns.

As socioeconomic slang, "salaryman" refers to the middle-aged man with a mortgage and a car and 1.5 kids who accepts his station in life in exchange for job security. Shall We Dance is about a man who's hit all the milestones and doesn't know what to do next.

Especially these days, it'll take an Alex P. Keaton about ten years to get there.

Eugene: Unlike Great Britain and like the U.S., Japan has a "unified" system (no distinction between barristers and solicitors). However, because trials are so rare, trial lawyers are more comparable to appellate lawyers in the U.S. And Japan allows professionals to work in specialized areas like tax and patent law without being lawyers.Kate: Although Shiro doesn't live the life of a salaryman, he is still expected to adhere to certain social expectations! In one volume, Shiro has to attend the wedding of a fellow lawyer. She comes from a good family and is marrying someone from a wealthy family. Shiro and his cooking friend, a married woman who buys food on sale and splits it with Shiro, commiserate on what a pain this all is. Shiro MUST contribute a large amount of "gift money" simply because of who these people are and where they are getting married. He and his friend have this exchange:

Because the bar exam is so tough, many students graduate from law school without ever intending or attempting to become members of the bar. However, it is hypothetically possible to pass the bar exam and become a lawyer without going to law school or even to college. That's the premise of Hero.

Shiro: For an instructor at a training institution, the rule of thumb is that "2" suffices, but I'm not an instructor, just her senior at a workplace.

Kayoko: So that means this much (she holds up all five fingers of one hand).

Kate: Yikes! The whole gift-giving pressure reminds me of numerous baby showers I've been invited to attend. I finally stopped since I couldn’t afford to keep buying so many gifts.Eugene: Gift giving is one of those customs that makes you happy to be a foreigner when in Japan. It's an arcane and socially complex minefield that is still going strong. Here’s a handy guide: Japan Gift Giving Customs

But suppose my ability to keep my job was tied into these baby showers? I would be scraping the bottom of my paycheck on a continual basis! Is this fair? Do the Japanese ever complain about this? In a noisier fashion than Shiro? (He goes to the wedding, but he and Kenji plan to eat lots of mackerel to keep within their monthly budget.)

Eugene: Yes, Japanese gripe about the pressures and obligations. Politicians and doctors (yes, doctors) get into trouble when the gift giving strays over the line into bribery, though where that line is can be hard to tell, and thus becomes an unending source of scandals.

No comments:

Post a Comment