|

| First Christmas Card 1843 |

Re-post.

The History

As writers like Nissenbaum have pointed out, the current celebration part of Christmas is a nineteenth-century creation. The Puritans associated Christmas with high Anglicanism and paganism (or rather, they associated anything associated with high Anglicanism with paganism).

The Victorians enjoyed Christmas, and Queen Victoria introduced German customs, but the huge decoration-explosion Nutcracker version of Christmas took awhile to catch on and didn't catch on in America (that home to "low" Protestantism) until the latter half of the nineteenth century. Santa Clause arrived around the same time.

The Victorians enjoyed Christmas, and Queen Victoria introduced German customs, but the huge decoration-explosion Nutcracker version of Christmas took awhile to catch on and didn't catch on in America (that home to "low" Protestantism) until the latter half of the nineteenth century. Santa Clause arrived around the same time.

Washington Irving used the Santa Clause image in his fiction, and Clement C. Moore--a friend of Irving's--practically invented the standard description with "A Visit From Saint Nicholas." In Moore's poem, Santa has a "broad face and a little round belly/That shook when he laughed, like a bowlful of jelly/He was chubby and plump." He also smokes. Moore additionally named Santa's reindeer (although Rudolf wasn't added until 1920). Other than Irving and Moore, the man who truly popularized the Santa Clause image in America was Thomas Nast, a German-born illustrator. (Both Irving and Moore also have German or, rather, Dutch connections.) Nast created his illustrations for Harper's Weekly (amongst other magazines) between 1860 to 1890. As well as Santa Clause, Nast is responsible for the donkey and the elephant as Democrat and Republican symbols; Nast is definitely an example of "high" or at least medium culture seeping into the lore of a nation. Rather impressive influence for one guy!

Other than Irving and Moore, the man who truly popularized the Santa Clause image in America was Thomas Nast, a German-born illustrator. (Both Irving and Moore also have German or, rather, Dutch connections.) Nast created his illustrations for Harper's Weekly (amongst other magazines) between 1860 to 1890. As well as Santa Clause, Nast is responsible for the donkey and the elephant as Democrat and Republican symbols; Nast is definitely an example of "high" or at least medium culture seeping into the lore of a nation. Rather impressive influence for one guy! The Nast/Moore/American image of Santa is different from British versions: for a comparison, check out Lewis's description of Father Christmas in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Like Nast and unlike Moore, Lewis makes no overt attempt to associate Father Christmas with Saint Nicholas. Father Christmas has deep roots; it is likely that Saint Nicholas became a custodian for older stories, a common occurrence with Saints. C.S. Lewis would have been aware of the pagan element and he was more likely to incorporate paganism into his writing than excise or abolish it.

The Nast/Moore/American image of Santa is different from British versions: for a comparison, check out Lewis's description of Father Christmas in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Like Nast and unlike Moore, Lewis makes no overt attempt to associate Father Christmas with Saint Nicholas. Father Christmas has deep roots; it is likely that Saint Nicholas became a custodian for older stories, a common occurrence with Saints. C.S. Lewis would have been aware of the pagan element and he was more likely to incorporate paganism into his writing than excise or abolish it.

Kids and Santa

There are many folk stories and performances surrounding Santa, the most prevalent being that children should be allowed to believe in Santa as long as possible. Pretending Santa exists is a deliberate, uh, fib that kind parents allow their children to believe for the sake of the holiday.

And I sort of get it. Except when I don't. Believing in Santa, at least for me, wasn't exactly the same as believing in, say, aliens. (Aliens might be out there--I just don't think they would bother with Earth.) I asked my mom if Santa was real when I was about five. Some kids at the bus stop had told me he wasn't. I already knew the answer, so when she reluctantly said, "No," I didn't have a fit and start crying. I went, "Oh, okay."

On the other hand, it would have been nice if I could have believed some jolly, rich, old uncle was paying for the gifts under the Christmas tree. I was the kind of kid who felt guilty about everything (and I mean, everything) and naturally, the money my parents spent on my gifts got added to the list.

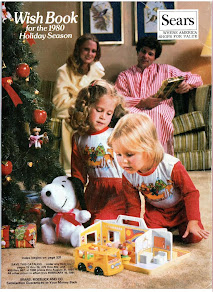

On the other other hand, I can't imagine pushing the idea of Santa Clause on anyone very hard. People in my childhood home talked about Santa, we selected gifts for our Santa lists from the Sears Roebuck catalog, and I put out milk and cookies (although that was more of a joke), but my parents never presented Santa as an actual possibility. "Santa" always seemed to be said in inverted commas. Even before my fifth year, I never believed in a North Pole hide-out or reindeer or a guy sliding down the chimney. I didn't not believe. I just didn't have any reason to believe (other than the guilt thing).

Do kids believe? Or do they really know, in their heart of hearts, that Santa is the head of the household? Do parents still spin elaborate tales about Santa's time traveling abilities? Or has Santa become an image and only an image: have your picture taken with the red-coated symbol?

Literary/Popular Appearances

Clement C. Moore's "A Visit From St. Nicholas" naturally. Grinch in How The Grinch Stole Christmas wears the traditional Santa Clause outfit. The awesome Bones episode "The Santa in the Slush" uses multiple red-coated singing Santas (with bells), and there's a very funny Due South episode where a number of Santas, reindeer, and Elvises ("I said elves, you fools! ELVES!") wander around the police station.

Clement C. Moore's "A Visit From St. Nicholas" naturally. Grinch in How The Grinch Stole Christmas wears the traditional Santa Clause outfit. The awesome Bones episode "The Santa in the Slush" uses multiple red-coated singing Santas (with bells), and there's a very funny Due South episode where a number of Santas, reindeer, and Elvises ("I said elves, you fools! ELVES!") wander around the police station.

Whatever the image--symbolic or decorative--Santa adds a lot to the festivities!

5 comments:

Santa was a reality TV show character before TV was invented.

I cringe when spiritual truths are associated with Santa but I'm a softy when it comes to buying the notion that a jolly fat guy in a red suit can deliver cool gifts throughout the world, all on a single night. And that's true when I'm the one doing the buying!

I've been pondering "A visit from st. nick" again lately, and I saw something I never really realized before... the narrator describes the sleigh as "miniature" and the reindeer and "tiny," he also refers to st. nick as small, and an "elf."

It may just be me, but it seems as the the narrator was trying to describe a character who was a traditional elf... very small. There is no wording in the poem to describe St. nick and reindeer as ordinary size, other than the narrator's ability to hear the reindeer on the roof.

I don't know... I can't find anything to back up my interpretation... what do you think?

I think you're right, Mike! In fact, the image in Moore's poem reminds me of the gnomes in Huygen's book. The gnomes are Scandinavian or Dutch (rather than English).

I was able to discover one 1912 version with a gnome-size Santa (illustrator, Jesse Willcox Smith). On the one hand, the prevalence of the large Santa image shows the power of folklore. On the other hand, my reaction is, "Geez, people, be a little more creative!"

And when it comes to sliding down chimneys, a gnome--rather than, say, Tim Allen--makes a lot more sense!

I believed in Santa Claus long after the usual age of disbelief. I believed because I wanted to. This wasn't belief in a department store Santa (rare in my childhood at the end of the Great Depression) or the Santa in the annual Christmas parade. They were obviously just someone dressed up in a costume. I believed in the real Santa--the bearded little man in a red suit who climbed through our window (we didn't have a fireplace) and left gifts.

I loved Christmas and this part of Christmas. I "knew" the truth even before my girlfriend told me that there was no Santa. But I believed anyway. I can remember hearing my older brother saying that Jesus was really born in April. I had a vivid dream that night that Santa couldn't come because there was no snow on which the sleigh could travel.

As I grew older I came to love the nativity story and was happy to have Jesus born in the spring. This belief was never confused with Santa. But when I first read The Polar Express I knew I had met a fellow Santa believer.

My parents never told me Santa was real. They believed it distracted from the religious elements of Christmas. They weren't hostile to it though, unlike some Fundamentalists I knew. They just were up front about it not being real. I think I ended up with a belief in him by osmosis, though like you I was okay when I found out (really young) he wasn't real.

Post a Comment