|

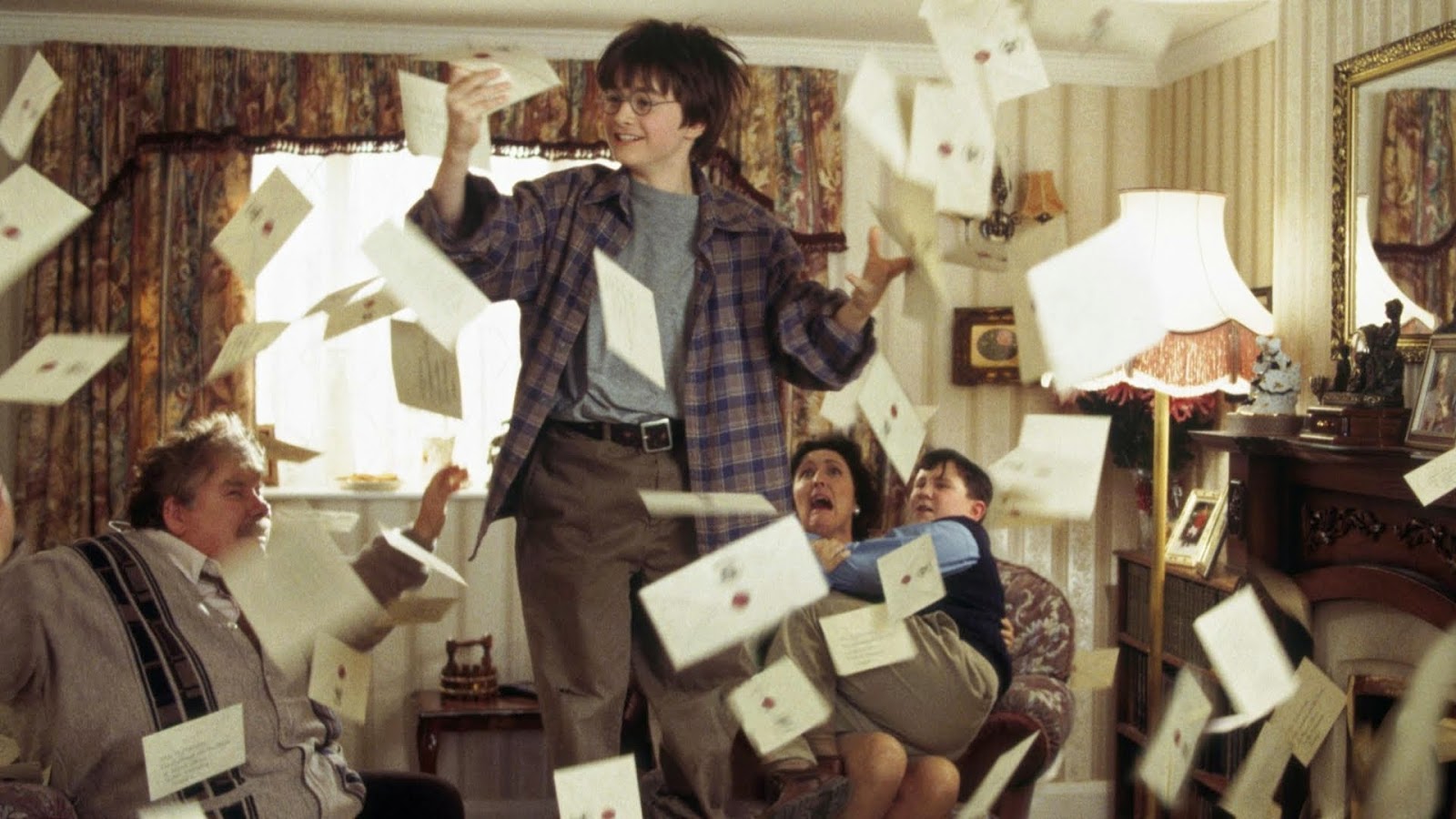

| Lovely image in a slideshow movie. |

To start:

The Slideshow or Strict Rendering

This is the most boring of the approaches and only slightly less pointless than "all we used was the title." It can usually be traced to a basic fallacy: books = movies.

No, no, they don't.

It is not only utterly unfair to expect a movie to be a clone of a book, it is utterly unfair to judge a movie/television episode by the same criteria as a book as I discuss in my post "Getting Snarky About Television and Other Anti-Television Silliness".

In sum, watching a movie utilizes one's imagination differently than reading a book.

This reality creates problems for readers who think that the imaginative journey they took in the book--"I could recreate the characters and the world in my own way!"--ought to be echoed by the movie.

|

| A non-slideshow movie. |

Of course, it's great to watch a movie where the characters and the setting are what one imagined. It simply isn't the point. The imaginative leap evoked by movies is NOT about turning words-into-images. The imaginative leap evoked by movies is about sensory immersion, no immediate left-brained translation.

What a movie asks for in terms of imagination isn't better or worse than what books ask for. It is different. But it's a difference that matters because when a movie tries to be a book, it fails--it stops being a movie and becomes a slideshow.

Slideshow movies come about when adherence to plot cancels out the director's interpretation or worldview. Harry Potter & the Sorcerer's Stone is a slideshow movie. Chris Columbus is not one for grand interpretations, yet Harry Potter the First lacks even his frenetic viewpoint.

|

| Chamber of Secrets |

Columbus did much better with the second movie, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. His imprint, especially in the chamber scenes, is more apparent.

|

| Pattinson before Twilight! |

To be more than a slideshow, a movie must have an authorial point of view and that authorial point must be the author of the medium (the director/ producer/ actors). Without a point of view . . . I might as well read the book. Such resignation might make "books only" folks happy; unfortunately, it would spell the death of an entire art-form.

7 comments:

Perhaps it is my profession in which fidelity to the text is critical, but I disagree. In the first place, it is possible to be faithful to a given text and yet still provide a specific viewpoint. I go back to the Firth/Ehle Pride & Prejudice, which is not in my opinion as boring as a slide show, is incredibly faithful to the text, and yet presents a specific video interpretation of that text.

When a movie tries to be a book, yes, it fails. It isn't a book. But neither should the movie rewrite the book. I went to see a video interpretation of Tolkien's book. Instead, I got Peter Jackson's book with Tolkien's characters. It may have been a decent movie, but it wasn't the same story. He told the same story Tolkien told in Fellowship of the Rings, mostly the same story in Two Towers, and his own story in Return of the King. By the middle of the first Hobbit movie, Jackson was on to his own story again.

I preferred Tolkien's.

I define "strict rendering" as separate from "interpretation," even a faithful interpretation. I'll go into more detail when I address the second category, but I totally agree that 1995 Pride & Prejudice is a faithful interpretation.

A strict rendering, in my mind, is when the scriptwriters and directors try to translate the book page by page to the screen. Some things just don't bridge that gap: inner dialog, for example, has to be translated into conversation or into a visual or provided through voice-over, which has its own problems. Austen's objective voice is almost impossible to recreate although the ending to Emma (1996) with Juliet Stevenson's marvelous wink at the camera comes close. In fact, Emma is a great example. I've seen three versions that all kept pretty close to the text, and all three were totally different in tone!

And theme! But I should wait for my next post . . . :)

Different media require different renderings, I will grant. A strict rendering is often little more than adding pictures - moving pictures, but pictures - to a reading of the book. Some of the earlier approaches to the Narnia Chronicles took this approach and they were so tied to the text there was little point to the pictures.

But I do much prefer a faithful rendering and I do not consider the Peter Jackson rendering of The Hobbit to be so. He did more than just borrow the title, but neither did he tell Tolkien's story.

I suppose this is in part a matter of taste. When it comes to visual arts of all sorts - paintings, photography, movies, sculpture - the art I prefer is the art in which the object is more important than the subject. Picasso never floated my boat because his art is so thoroughly him. Rembrandt, Monet, even Van Gogh - the artist/subject is definitely evident in their art, but as background and support to the art/object created. Picasso drew attention to Picasso. Monet drew attention to the lilies.

I do think that art should carry viewers/readers beyond themselves rather than focus on the fact that it is art. However, I think there are two other factors: (1) we viewers/readers must allow ourselves to be swept up without expectations or comparisons (easier said than done) and (2) the art should have something to give, whether that something is pleasure or profundity or amusement or insight into the human condition. The author hides but that author's viewpoint is absolutely necessary to the thing being art (at all). Without Monet, the lilies would not be memorable.

I address faithful interpretations in my latest post!

Yes - the artist helps to make the object memorable, and worth remembering. And it is in doing so that the artist/subject may become memorable and worth remembering. I don't think nearly as many people would care about Tolkien if he wrote about Tolkien, nor would Ben Franklin's autobiography be of interest if his prior artistry had not sparked that interest. The self-portrait is only worthwhile if the other portraits are good first.

I agree! In fact, I find that I enjoy biographies that focus on the writer, artist, or actor's process much more than biographies that deliver "he lived here" information or (in the case of actors) gossip derived from celebrity magazines.

T.A. Shippey's Tolkien: Author of the Century is a good example of a book that concentrates on the man and his creation. So is The Narnian by Alan Jacobs about C.S. Lewis.

Post a Comment