What I read: The Expedition of Cyrus by Xenophon

I'm never going to be a classicist because I like more dialog in my exposition. Book 1 of The Expedition is straight exposition. It's kind of like reading Numbers in the Bible: lists of generals and numbers of troops. It's like watching a Risk game. Shoot, it's like playing Risk. (Most boring board game ever invented.)

However, about half-way through Book 1, Cyrus dies, and Xenophon (who was there, but refers to himself in the third person) goes into this long panegyric about what a great guy Cyrus was and how he would have been a WAY better king than his brother, thank you very much, and this is actually pretty interesting stuff as well as being great argument/persuasion. Here's a guy who knows how to argue his point (and is totally direct about it).

And there are some interesting nuggets. One is the description of the battle. You know those fantasy/ancient legend types of movies where the two sides line up in a really, really, really long line and rush each other? Turns out, the ancient Mediterranean people actually did that, and it sounds pretty exciting!

Another is Xenophon's historical persona. It isn't as if he footnotes his "data." But he doesn't jump to conclusions. At one point, Cyrus is "betrayed" by one of his Persian backers, Orontas. Orontas goes to trial and then "was taken into the tent of Artapatas, the most loyal of Cyrus' staff-bearers, and no one ever again saw Orontas alive or dead, nor could anyone say with certainty how he died, although people came up with various conjectures. No one ever saw his grave either." It isn't clear whether Xenophon is trying a little too hard to NOT make Cyrus seem like a butchering murderer or whether Xenophon is actually doubtful whether the whole thing wasn't just an elaborate show, and Cyrus really let the guy live. In any case, it's fun historical writing!

Another interesting tid-bit is how xenophobic (another "X"!) those Greeks were. Cyrus hired a bunch of Greeks to go fight with him against the Persian army controlled by his brother. The Greeks were mercenaries, yet Xenophon, a Greek, continually refers to the Persian army as "barbarians." He's completely unapologetic about it. That's what barbarians do. Yep, the barbarians are at it again.The lowliest Greek is better than the Persian king: there's something awe-inspiring about this attitude.

2023: I learned about Xenophon. I read the introduction to another of his books, Hellenica. I also watched Great Course's The Greek and Persian Wars with Professor John R. Hale.

|

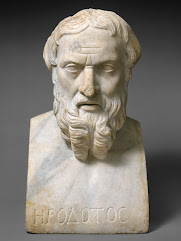

| Herodotus |

1 comment:

Don't bother with 300; it's one of the dumbest movies I've ever suffered through.

Post a Comment