What I read: Grover G. Graham and Me by Mary Quattlebaum.

There aren't many "Q's" when it comes to fiction authors. I'm sure there are loads of "Q" fiction authors in the Library of Congress, but "Q's" in local libraries tend to occupy one to two shelves--at the most. At my local library, I found Quattlebaum, and I decided that anyone with such an awesome last name deserved to be read!

The book is quite good. It belongs in the category, "Fiction about orphan/foster children." Cynthia Voigt's Homecoming series comes to mind. Grover G. Graham and Me is told from a young foster boy's point of view. He is on foster home number eight or nine. There he encounters a toddler who reminds him of himself (this is never stated directly) and decides to rescue the toddler when the seemingly irresponsible mother comes to reclaim him.

|

| Harper Lee's novel is remarkable: |

| she retains the child's voice yet adult |

| readers can winnow out more. |

The rescue part of the book is actually, realistically, quite short. It would have been interesting to see if the boy could have survived with the toddler for more than a day, but the book is really about the boy deciding to set down roots, not about the kidnapping.

Kids' Thoughts

The only slight snag is the boy's voice, a common problem with books told from a child's point of view. How do you make the child sound like a child without making him or her sound, well, boring? I'm not sure that children are too different from my cats: I'm hungry. I'm bored. Is there anything to do? Are we there yet? Can I go out and play?

I mean, how much critical thinking actually goes on? I don't remember much in-depth philosophical contemplation from my own prepubescence, though I do remember certain breath-taking decisions about God and theology (though I didn't use the latter word) between the ages of five to twelve but these were decisions/ideas, not developed ideologies.

On the other hand, C.S. Lewis provides his children with far more authority than your average child has--which is kind of the point. But "realistic" fiction can't make that trade-off. In real life, children don't have power. Consequently, "realistic" children are often given far more introspective thoughts about their powerlessness than I think they probably have. Most children are more like Billy Collins' "Lanyard" kid: Reality is whatever I'm doing right now.

But then, a lack of introspection would make such books pretty uninteresting. When I'm reading books of this type, I simply increase the age of the heroes or heroines in my mind: the hero isn't eleven, I tell myself; he's fifteen. In my own story with a boy of about thirteen, I made that narrator an adult, looking back at his child self.

I will be tackling Quattlebaum for the Fairy Tale list!

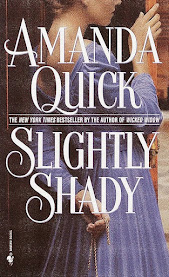

2023: I decided to read a "Q" book from adult fiction and settled on Amanda Quick, a romance writer. I've read a great many romance books over the years, but Amanda Quick is one I've usually skipped.

I chose Slightly Shady because it has an investigation. The investigators, Lavinia Lake and Tobias March, fall in love. Although the investigation was of a "powerful villain [of] a vast criminal organization" (which plot line bores me almost as much as conspiracy theories and drug tales), the same investigators appear in a later book, so I thought, "Hey, why not?"

I found the investigation more interesting than the characters.

Lake and March, unfortunately (in this book at least), fall into the category of enemies to lovers who jump from bickering and arguing to kissing and other intimacies within less than a page and then jump back again. They are always going at each other about something.

When I read books with such characters, I wonder if the authors watch shows like Bones and fail to get anything out of the episodes beyond the bickering. Bones is graced not just by the initial arguments or disagreements or even the Thin Man repartee. It is graced by understanding and acceptance. The arguments--if they even rise to that level--are about insight and growth.

In Season 1 "The Man in the Bear," both Brennan and Booth are amused by the same things. In "The Man on Death Row" and "The Girl in the Fridge," Brennan and Booth demonstrate a strong understanding and respect for the other's ethics: what motivates that person. Their mutual knowledge expands until Brennan can say without hesitation to Booth, "I knew you would [fulfill my promise]. I knew you wouldn't make me a liar."

In Season 1 "The Man in the Bear," both Brennan and Booth are amused by the same things. In "The Man on Death Row" and "The Girl in the Fridge," Brennan and Booth demonstrate a strong understanding and respect for the other's ethics: what motivates that person. Their mutual knowledge expands until Brennan can say without hesitation to Booth, "I knew you would [fulfill my promise]. I knew you wouldn't make me a liar." That is, the relationship changes--even in Season 1--even within the pilot--as the two become closer and gain insights and thrive in each other's presence. It is NOT a constant yo-yo of argue-argue-argue-make-out-argue-argue-argue.

|

| The bickering in The Thin Man is never |

| about hierarchy. There's the case to solve! |

Constant fighting doesn't preclude mutual attraction, of course, and the suggestion of "wow, we can't stand each other but we do work well together--and then there's the sex" in Quick's book would have been somewhat interesting.

That is not the direction the series is going.

I may try a second book with the same characters, simply to see if they become less annoying once they are hitched.

No comments:

Post a Comment